Whatever you call it, you can’t live without it … and we just got a new one. But, I had no idea it was going to be such a challenging purchase. Assuming you have a specific size and know you need it to be fueled by gas or electricity (or do you want duel-fuel), you then have to decide between a cooktop, built-in, free-standing, drop-in or slide-in range. Now, if you want an electric stove, do you want coil or induction? If its gas, how many btu’s do you need? How many burners? A standard 4 or maybe 6? Or how about a built-in griddle that doubles as two burners?

Then, of course, comes the design … do you want the controls in the front or the back? Or would you prefer a touch screen? What about baking … conventional or convection? How many oven compartments do you want? Do you want them to cook at the same or different temperatures? Do you want a broiler drawer, warming drawer or storage drawer? What about a temperature probe? And we haven’t even started to talk about finishes …

It was so confusing … but what I really wanted was a classic, cast-iron English AGA cooker. I’d be surprised if you’re not familiar with this icon of a cooker. For over 100 years, the AGA has commanded attention in most English kitchens, from the largest manor houses to the more modest cottages. Chefs including Marco Pierre White, Paul Hollywood and Mary Berry wouldn’t think of cooking on anything else. Jamie Oliver said AGAs “make people better cooks”. Food writer, William Sitwell, said using one was a “much more natural way of cooking”, and actor Gerard Depardieu describes his AGA simply as “fabulous”.

It was so confusing … but what I really wanted was a classic, cast-iron English AGA cooker. I’d be surprised if you’re not familiar with this icon of a cooker. For over 100 years, the AGA has commanded attention in most English kitchens, from the largest manor houses to the more modest cottages. Chefs including Marco Pierre White, Paul Hollywood and Mary Berry wouldn’t think of cooking on anything else. Jamie Oliver said AGAs “make people better cooks”. Food writer, William Sitwell, said using one was a “much more natural way of cooking”, and actor Gerard Depardieu describes his AGA simply as “fabulous”.

Although the AGA has been a British icon for decades, it was invented and originally manufactured in Sweden. Its inventor was a Swedish physicist, Dr. Gustaf Dalén. Dalén was a brilliant, self-taught inventor who began his impressive career managing the family farm. His first invention was a machine to test the quality of milk. That invention alone caught the eye of others who encouraged him to get a formal education. Gustaf went on to earn a Masters and subsequently a Doctorate degree, earning a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1912.

Gustaf Dalen, Managing Director of AGA – 1926

Gustaf became employed by the Svenska Aktiebolaget Gas Accumulator company in 1906 and within three years became Managing Director. Dalén worked exclusively with a highly flammable and sometimes explosive hydrocarbon gas. This hydrocarbon gas produced a bright white light perfect for illuminating lighthouses. This important safety device for the fishing and shipping industries led the way for similar products for lighthouses . . . the Dalén Light, the Sun Valve and then the Dalén Flasher, a device which created a small pilot light, reducing gas consumption by 90%. These inventions were a huge success and AGA lighthouses were mass- produced and sold all over the world.

Unfortunately, in 1912 during a test for one of these highly-flammable devices, an explosion occurred which caused Gustaf to lose his sight. This physical setback did not deter him, however. Over the course of his lifetime he had over 100 successful patented inventions . . . his most memorable was the AGA cooker.

Although there were many styles of British ranges being used, from wood to coal fired, they tended to be dirty, time consuming and, occasionally, dangerous. They had ovens to bake in and hot plates to simmer things on and they kept the kitchen toasty warm. For proper venting, the ranges needed to be installed into a fireplace opening. The biggest disadvantage was soot falling down the chimney into the food, and the amount of work it took to clean them. The range had to be cleaned every day, carefully removing the ashes and cinders, which were still combustible. The oven had to be swept out, and any grease which splattered needed to be scraped off. The flue needed to be cleaned constantly.

Although there were many styles of British ranges being used, from wood to coal fired, they tended to be dirty, time consuming and, occasionally, dangerous. They had ovens to bake in and hot plates to simmer things on and they kept the kitchen toasty warm. For proper venting, the ranges needed to be installed into a fireplace opening. The biggest disadvantage was soot falling down the chimney into the food, and the amount of work it took to clean them. The range had to be cleaned every day, carefully removing the ashes and cinders, which were still combustible. The oven had to be swept out, and any grease which splattered needed to be scraped off. The flue needed to be cleaned constantly.

Gustaf’s wife, Elma, was in the kitchen cooking on a typical soot-producing, dirty and sometimes very dangerous coal-fired range. Realizing that this was not only dirty, dangerous and incredibly time consuming to use, Gustaf began conceiving a new style of cooker. He wanted one that was clean, easy-to-use, economical and not at all dangerous. Using the principle of heat storage, Dalén combined a heat source, two large hotplates and two ovens in one cast-iron cooker. In doing so, he invented a range that changed the lives of cooks not only in Great Britain but all over the world.

AGA cooker. Circa 1939

Originally manufactured in Sweden, the AGA cooker wasn’t introduced to England until 1929, but it didn’t reach its height of popularity until after World War II. During the war years, the British government used AGA cookers in feeding centers, hospitals and munitions factories, and the public fell in love with them. After that, the demand for these cookers skyrocketed and manufacturing moved from Sweden to England . . . where they are still made today.

Over the years, as with other ranges, much has changed. Today, depending upon the model, this massive beast of a cooker can have from two to six oven compartments, and from one to two hot plates on top (or the hob). It is available as gas-fueled or by electricity. You also have as many decisions to make as I’ve had to make in purchasing my new not-AGA range. But, whichever size, model, color, options, etc. you choose, you can be sure you’ve made a lifetime purchase.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

References: Wikipedia, Cosi, House Logic, Victorian Decorating, 1900s, AGAliving,

_____________________________________________________________________________

I actually remember “dish night” at the movie theaters. A very popular promotional event where movie theaters would give away a dish to get theater goers to come in on a slow night. If you went to the movies often enough, it was possible to collect a complete set. In the 1970s supermarkets used this same type of promotion with “Blue Willow”, giving away a different piece each week based upon how much money you spent. Before long, you had the complete set. Blue Willow wasn’t the only pattern given away. Another very popular chinaware was various scenes from Currier & Ives, as well as Blue Liberty.

I actually remember “dish night” at the movie theaters. A very popular promotional event where movie theaters would give away a dish to get theater goers to come in on a slow night. If you went to the movies often enough, it was possible to collect a complete set. In the 1970s supermarkets used this same type of promotion with “Blue Willow”, giving away a different piece each week based upon how much money you spent. Before long, you had the complete set. Blue Willow wasn’t the only pattern given away. Another very popular chinaware was various scenes from Currier & Ives, as well as Blue Liberty.

We booked the experience in the beautiful countryside of North Yorkshire. Pulling up to the castle, there they were, a fleet of white vehicles all lined up and ready for you to take out. After all the necessary paperwork, licenses, waivers, etc., we were introduced to our co-pilot and handed the keys. Our personable instructor could not have been more experienced or a better host. Fully versed in all the vehicles capabilities, off we went onto Mother Nature’s “track”, with our qualified co-pilot up front, hubby nervously driving and me tucked safely away in the back.

We booked the experience in the beautiful countryside of North Yorkshire. Pulling up to the castle, there they were, a fleet of white vehicles all lined up and ready for you to take out. After all the necessary paperwork, licenses, waivers, etc., we were introduced to our co-pilot and handed the keys. Our personable instructor could not have been more experienced or a better host. Fully versed in all the vehicles capabilities, off we went onto Mother Nature’s “track”, with our qualified co-pilot up front, hubby nervously driving and me tucked safely away in the back. Starting the drive, you’re taken in by the beauty of the area, from dense, lush forests to open fields and pastures. You can spot deer who perk up when they hear the automobile coming. Pheasant and grouse dart across the terrain. It’s quite beautiful.

Starting the drive, you’re taken in by the beauty of the area, from dense, lush forests to open fields and pastures. You can spot deer who perk up when they hear the automobile coming. Pheasant and grouse dart across the terrain. It’s quite beautiful.

I love all things tea … from the origins of the leaf to the ritualistic preparations, the variety of ethnic traditions, as well as the fascinating accoutrements. For preparation, the simple unadorned, unpretentious Brown Betty is one of my favorite teapots. I know its a name that is familiar to a lot of tea drinkers, but I wonder if anyone knows how this modest, round-bellied pot got its name and why some devout tea drinkers think it the only vessel worthy of steeping a perfect cuppa.

I love all things tea … from the origins of the leaf to the ritualistic preparations, the variety of ethnic traditions, as well as the fascinating accoutrements. For preparation, the simple unadorned, unpretentious Brown Betty is one of my favorite teapots. I know its a name that is familiar to a lot of tea drinkers, but I wonder if anyone knows how this modest, round-bellied pot got its name and why some devout tea drinkers think it the only vessel worthy of steeping a perfect cuppa.

During the Victorian era, every affluent household had servants. In the grander homes, there were servants who worked “downstairs” and servants who worked “upstairs”. The “downstairs” servants generally were not known by their name and were usually referred to by their job, “cook” or “boots”, but the “upstairs” servants were well known to the lords and ladies of the house and would probably be referred to by a ‘nick name’. MaryJane would become “Mary”. Abigail would become “Abby”. Elizabeth would become “Betty”.

During the Victorian era, every affluent household had servants. In the grander homes, there were servants who worked “downstairs” and servants who worked “upstairs”. The “downstairs” servants generally were not known by their name and were usually referred to by their job, “cook” or “boots”, but the “upstairs” servants were well known to the lords and ladies of the house and would probably be referred to by a ‘nick name’. MaryJane would become “Mary”. Abigail would become “Abby”. Elizabeth would become “Betty”. By the mid-1800s, with many Staffordshire Pottery factories producing them, the teapot had evolved somewhat and became considerably more affordable. And by 1926, it was estimated that the industry was producing approximately 500,000 Brown Betty Teapots per week … making it the most popular, widely used teapot in the country.

By the mid-1800s, with many Staffordshire Pottery factories producing them, the teapot had evolved somewhat and became considerably more affordable. And by 1926, it was estimated that the industry was producing approximately 500,000 Brown Betty Teapots per week … making it the most popular, widely used teapot in the country.

Legend tells us that more than 5,000 years ago, the Chinese emperor, Shen Nung, was sitting under a tree in his garden boiling water when the wind picked up and leaves from the tree drifted down into his pot. Intrigued by the fragrant aroma and beauty of the golden liquid, he drank the infusion and enjoyed it. Tea has played a vital role in the Chinese culture ever since.

Legend tells us that more than 5,000 years ago, the Chinese emperor, Shen Nung, was sitting under a tree in his garden boiling water when the wind picked up and leaves from the tree drifted down into his pot. Intrigued by the fragrant aroma and beauty of the golden liquid, he drank the infusion and enjoyed it. Tea has played a vital role in the Chinese culture ever since. Why is this important? Because China is a very large country, with different languages spoken in different regions, and depending upon the port from which the tea was shipped, is how this beverage got its name.

Why is this important? Because China is a very large country, with different languages spoken in different regions, and depending upon the port from which the tea was shipped, is how this beverage got its name.

The southern trade route, which was discovered by the Portuguese in the 15th century, actually introduced England to tea. This dangerous and long voyage traveled from China through Java to Europe around the Cape of Good Hope up the coast of Africa to Europe. It was these very same Portuguese and Dutch traders who first imported tea … “te” … into Europe. Regular shipments of “te” had begun reaching England by 1610. And with the use of Clipper ships, traveling at over 250 miles a day, the race was on.

The southern trade route, which was discovered by the Portuguese in the 15th century, actually introduced England to tea. This dangerous and long voyage traveled from China through Java to Europe around the Cape of Good Hope up the coast of Africa to Europe. It was these very same Portuguese and Dutch traders who first imported tea … “te” … into Europe. Regular shipments of “te” had begun reaching England by 1610. And with the use of Clipper ships, traveling at over 250 miles a day, the race was on.

I’ve read that the first known recipe for ‘gingerbrede’ came from Greece in 2400 BC. Really? How do they know that? I do know, however, that food historians have traced ginger as a seasoning since antiquity. From my research, it seems an Archbishop from Armenia, in the 1st century, is credited with serving his guests a cake made of spices. By the tenth century, its proven that Chinese recipes for ‘spice breads’ were developed using ginger, and by the 13th century European nuns in monasteries were known to be baking ‘gingerbredes’ to ease indigestion. As spices, and in particular ginger, made their way throughout Northern and Western Europe, these breads baked in monasteries became so popular professional bakers began to make them. The ingredients, of course, were a bit different from what we would expect. Ground almonds, breadcrumbs, rosewater, sugar and ginger were mixed together and baked. It wasn’t until the 16th century when eggs and flour were added.

I’ve read that the first known recipe for ‘gingerbrede’ came from Greece in 2400 BC. Really? How do they know that? I do know, however, that food historians have traced ginger as a seasoning since antiquity. From my research, it seems an Archbishop from Armenia, in the 1st century, is credited with serving his guests a cake made of spices. By the tenth century, its proven that Chinese recipes for ‘spice breads’ were developed using ginger, and by the 13th century European nuns in monasteries were known to be baking ‘gingerbredes’ to ease indigestion. As spices, and in particular ginger, made their way throughout Northern and Western Europe, these breads baked in monasteries became so popular professional bakers began to make them. The ingredients, of course, were a bit different from what we would expect. Ground almonds, breadcrumbs, rosewater, sugar and ginger were mixed together and baked. It wasn’t until the 16th century when eggs and flour were added. Did you know Queen Elizabeth I is credited with creating the first “gingerbread man”? Known for her outlandish royal dinners, Queen Elizabeth employed a ‘Royal gingerbread baker’. Among her array of fancy desserts were not only birds, fruits, and castles shaped out of marzipan, but also of gingerbread. The first documented gingerbread-shaped biscuit actually came from the court of Queen Elizabeth when she commissioned figures to be made in the likeness of some of her important guests. They were the hit of the court and soon these biscuits made their way into the bakeries.

Did you know Queen Elizabeth I is credited with creating the first “gingerbread man”? Known for her outlandish royal dinners, Queen Elizabeth employed a ‘Royal gingerbread baker’. Among her array of fancy desserts were not only birds, fruits, and castles shaped out of marzipan, but also of gingerbread. The first documented gingerbread-shaped biscuit actually came from the court of Queen Elizabeth when she commissioned figures to be made in the likeness of some of her important guests. They were the hit of the court and soon these biscuits made their way into the bakeries. Elaborately decorated gingerbread became so synonymous with all things fancy and elegant that the Guilds began hiring master bakers to create works of art from gingerbread. Bakers began carving wooden boards to create elaborately designed molds to shape individual images. The shapes included not only flowers, birds, and animals, but even people. They were in such demand, kings and queens, lords and ladies, knights and bishops wanted their images captured in “gingerbread”. Should a young woman want to improve her chances of attracting a husband, she would have a “gingerbread man” made for her in the likeness of her gentleman’s image. The hope was that if she could get him to eat the spicy delicacy, he would then fall in love with her. Decorated gingerbread was given as a wedding gift, or to celebrate a birth or special occasion.

Elaborately decorated gingerbread became so synonymous with all things fancy and elegant that the Guilds began hiring master bakers to create works of art from gingerbread. Bakers began carving wooden boards to create elaborately designed molds to shape individual images. The shapes included not only flowers, birds, and animals, but even people. They were in such demand, kings and queens, lords and ladies, knights and bishops wanted their images captured in “gingerbread”. Should a young woman want to improve her chances of attracting a husband, she would have a “gingerbread man” made for her in the likeness of her gentleman’s image. The hope was that if she could get him to eat the spicy delicacy, he would then fall in love with her. Decorated gingerbread was given as a wedding gift, or to celebrate a birth or special occasion. In many European countries, gingerbread is still considered an art form, and the antique mold collections are on display in many museums. According to the Guiness Book of World Records, the largest gingerbread man was made in Norway in November 2009 and weighed 1,435 lbs. And the largest gingerbread house was made in Texas, November 2013 by the Traditions Club – 60 ft. long, 42 ft. wide and 10 ft. tall – all to raise money for St. Joseph’s Hospital.

In many European countries, gingerbread is still considered an art form, and the antique mold collections are on display in many museums. According to the Guiness Book of World Records, the largest gingerbread man was made in Norway in November 2009 and weighed 1,435 lbs. And the largest gingerbread house was made in Texas, November 2013 by the Traditions Club – 60 ft. long, 42 ft. wide and 10 ft. tall – all to raise money for St. Joseph’s Hospital.

Pearlies began in London in the early 1800s as ordinary “costermongers” or street vendors. The name “costermonger” comes from “costard” for apple and “monger” meaning seller. Often seen as vagrants and hounded by the police, these costermongers roamed the streets selling fruits and vegetables. Times were difficult and money hard to come by, but costers were always willing and eager to help each other out. Looked down upon by society and often bullied, they organized themselves into neighborhood groups for safety and elected Kings to lead them.

Pearlies began in London in the early 1800s as ordinary “costermongers” or street vendors. The name “costermonger” comes from “costard” for apple and “monger” meaning seller. Often seen as vagrants and hounded by the police, these costermongers roamed the streets selling fruits and vegetables. Times were difficult and money hard to come by, but costers were always willing and eager to help each other out. Looked down upon by society and often bullied, they organized themselves into neighborhood groups for safety and elected Kings to lead them. Henry Croft, orphaned at a very young age, became a street sweeper at age 13. Croft was fascinated by the costermongers and by their charitable lifestyle. He was also fascinated with their concept of adorning clothing with attention-getting buttons. Although there are many stories about how Croft came about obtaining his first set of mother-of-pearl buttons, the truth has been lost in time. What we do know is that in 1880, Croft with his good friend, George Dole, started sewing hundreds of mother-of-pearl buttons on a suit.

Henry Croft, orphaned at a very young age, became a street sweeper at age 13. Croft was fascinated by the costermongers and by their charitable lifestyle. He was also fascinated with their concept of adorning clothing with attention-getting buttons. Although there are many stories about how Croft came about obtaining his first set of mother-of-pearl buttons, the truth has been lost in time. What we do know is that in 1880, Croft with his good friend, George Dole, started sewing hundreds of mother-of-pearl buttons on a suit.

Make the filling first by dissolving a packet of orange-flavored gelatin into 1/3 cup of boiling water. Spray or grease a 12 count muffin tin. Into the bottom of each cup put a tablespoon of the gelatin. Put the tin into the refrigerator for the gelatin to set. When the gelatin has set completely, remove each disc from the muffin tin and place on a dish. Place the dish back into the refrigerator until its time to assemble.

Make the filling first by dissolving a packet of orange-flavored gelatin into 1/3 cup of boiling water. Spray or grease a 12 count muffin tin. Into the bottom of each cup put a tablespoon of the gelatin. Put the tin into the refrigerator for the gelatin to set. When the gelatin has set completely, remove each disc from the muffin tin and place on a dish. Place the dish back into the refrigerator until its time to assemble. Using a stand mixer or hand mixer, beat the eggs and sugar together for at least 5 minutes until delicate, pale and frothy. Sift together the flour, baking soda and salt. Carefully fold the dry ingredients into the egg mixture. Be careful not to deflate the eggs. Put 2 tablespoons of batter into the bottom of each of the greased muffin cups and bake at 350° for 7 to 8 minutes or until pale but baked through.

Using a stand mixer or hand mixer, beat the eggs and sugar together for at least 5 minutes until delicate, pale and frothy. Sift together the flour, baking soda and salt. Carefully fold the dry ingredients into the egg mixture. Be careful not to deflate the eggs. Put 2 tablespoons of batter into the bottom of each of the greased muffin cups and bake at 350° for 7 to 8 minutes or until pale but baked through. Remove the muffin pan from the oven and let cool for a few minutes. Then remove each cake/cookie and let them cool completely on a wire rack. Meanwhile, over a bowl of very hot water, melt the chocolate chips, stirring as necessary until smooth and shiny. Let cool a bit.

Remove the muffin pan from the oven and let cool for a few minutes. Then remove each cake/cookie and let them cool completely on a wire rack. Meanwhile, over a bowl of very hot water, melt the chocolate chips, stirring as necessary until smooth and shiny. Let cool a bit. To assemble: take a cake/cookie and place an orange disc on top and quickly place a spoonful of the chocolate on top of the disc. Using the back of a spoon, spread the chocolate, sealing in the orange wafer. Place the cookie back onto the rack. When they are all assembled, using the tines of a fork, gently make a criss-cross pattern on each of them*.

To assemble: take a cake/cookie and place an orange disc on top and quickly place a spoonful of the chocolate on top of the disc. Using the back of a spoon, spread the chocolate, sealing in the orange wafer. Place the cookie back onto the rack. When they are all assembled, using the tines of a fork, gently make a criss-cross pattern on each of them*. They may not be as pretty as Mary Berry’s Jaffa Cakes, but they taste pretty darn good. Tasty little cakes with an orange filling and chocolate frosting. If you wanted to make these ahead, I’m sure they’d probably last a few days, but definitely not in our house!

They may not be as pretty as Mary Berry’s Jaffa Cakes, but they taste pretty darn good. Tasty little cakes with an orange filling and chocolate frosting. If you wanted to make these ahead, I’m sure they’d probably last a few days, but definitely not in our house!

First, warm the milk in the microwave (not too hot) and stir in the yeast and the sugar. Let it rest for 10 minutes until its frothy.

First, warm the milk in the microwave (not too hot) and stir in the yeast and the sugar. Let it rest for 10 minutes until its frothy. In a large bowl, stir together the flours and the salt. Add the warm milk mixture and stir together until a thick dough forms. If using a stand mixer, use the paddle attachment. Let it mix for about 3 or 4 minutes.

In a large bowl, stir together the flours and the salt. Add the warm milk mixture and stir together until a thick dough forms. If using a stand mixer, use the paddle attachment. Let it mix for about 3 or 4 minutes. No need to take it out, knead it and grease the bowl. Just cover the bowl with a towel and put it aside to rise for about an hour, or until the dough has doubled in size.

No need to take it out, knead it and grease the bowl. Just cover the bowl with a towel and put it aside to rise for about an hour, or until the dough has doubled in size. When it has doubled and will hold an indentation from your finger, it’s ready. Mix together the cup of water with the baking soda. Now comes the tricky part, mix this liquid into the dough. It’ll be difficult at first. I used a fork to break the dough up, and then beat the mixture with a wooden spoon until it was somewhat smooth (but not perfect … still a bit lumpy).

When it has doubled and will hold an indentation from your finger, it’s ready. Mix together the cup of water with the baking soda. Now comes the tricky part, mix this liquid into the dough. It’ll be difficult at first. I used a fork to break the dough up, and then beat the mixture with a wooden spoon until it was somewhat smooth (but not perfect … still a bit lumpy). Using a ladle or tablespoon, spoon equal portions of the batter into the molds. The batter will be sticky and gloppy. Don’t be concerned. That’s how it’s suppose to be. Keep an eye on the heat to be sure they don’t burn on the bottom, turning it down as necessary. They will rise and as with pancakes, they will be almost fully cooked before they need to be flipped over (about 6 minutes on the first side). When the top has lost its gloss and the sides look firm, remove the rings. The rings will be hot, so use tongs. With a spatula, flip the crumpets over and let them cook on the other side for just another minute.

Using a ladle or tablespoon, spoon equal portions of the batter into the molds. The batter will be sticky and gloppy. Don’t be concerned. That’s how it’s suppose to be. Keep an eye on the heat to be sure they don’t burn on the bottom, turning it down as necessary. They will rise and as with pancakes, they will be almost fully cooked before they need to be flipped over (about 6 minutes on the first side). When the top has lost its gloss and the sides look firm, remove the rings. The rings will be hot, so use tongs. With a spatula, flip the crumpets over and let them cook on the other side for just another minute.

A Chatelaine is nothing more than a “key chain” … a key chain most often worn by women heads of households, but also some men, from early Roman times through to the 19th century. During this period, women’s clothing did not have pockets, and women did not carry handbags. Unthinkable, I know. So where did women (and some men) keep the keys to the larder or the tea chest? What about those small embroidery scissors or their watch? Not to mention their snuff box or perfume vial. This very practical accessory, the Chatelaine, would hold all of these and other essential items, which a head of house, a nanny, or nurse might need at a moment’s notice.

A Chatelaine is nothing more than a “key chain” … a key chain most often worn by women heads of households, but also some men, from early Roman times through to the 19th century. During this period, women’s clothing did not have pockets, and women did not carry handbags. Unthinkable, I know. So where did women (and some men) keep the keys to the larder or the tea chest? What about those small embroidery scissors or their watch? Not to mention their snuff box or perfume vial. This very practical accessory, the Chatelaine, would hold all of these and other essential items, which a head of house, a nanny, or nurse might need at a moment’s notice.

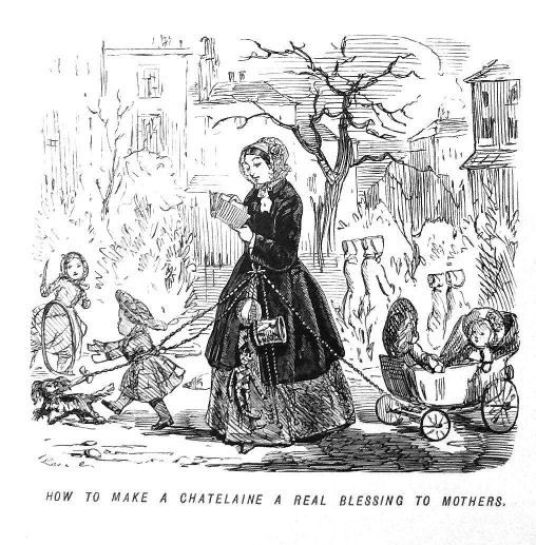

Punch, a very influential 19th century British weekly magazine, notorious for their sophisticated humor and satire (and is known for creating the “cartoon”), came up with an interesting use of the Chatelaine to aid mothers of young children

Punch, a very influential 19th century British weekly magazine, notorious for their sophisticated humor and satire (and is known for creating the “cartoon”), came up with an interesting use of the Chatelaine to aid mothers of young children As I mentioned above, Chatelaines are actually still very popular. Today’s Chatelaine may look a little different and some may be purely decorative, but not all. How many of us wear a Lanyard to hold our eyeglasses or company badge? This very practical accessory, the Lanyard, is also a modern day form of a Chatelaine.

As I mentioned above, Chatelaines are actually still very popular. Today’s Chatelaine may look a little different and some may be purely decorative, but not all. How many of us wear a Lanyard to hold our eyeglasses or company badge? This very practical accessory, the Lanyard, is also a modern day form of a Chatelaine.